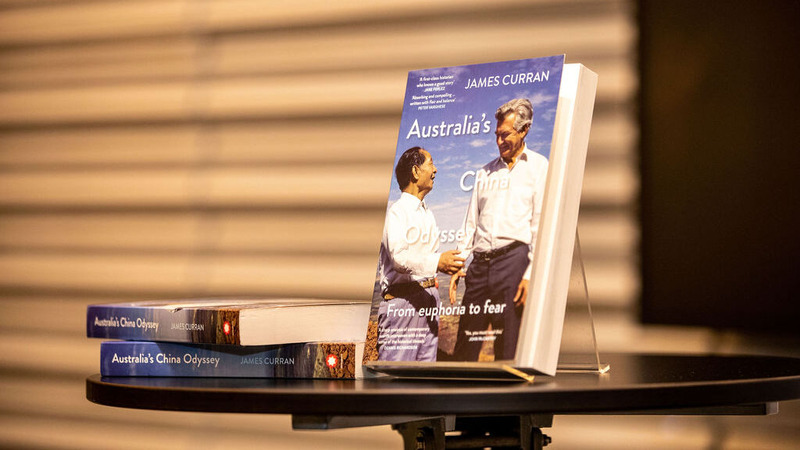

Review of Australia’s China Odyssey: From Euphoria to Fear

May 30 2023

Note: This article appeared in the Council on Foreign Relations' Asia Unbound on May 30 2023.

Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, addressing the National Press Club in April, said of Australia’s foreign policy choices, ‘We are not hostages to history. We decide what to do with the present.’ In saying this, she acknowledged that the past serves as a valuable guide, and in some cases a useful warning, in making strategic choices today.

Australia’s China Odyssey (2022) by University of Sydney historian and international editor at the Australian Financial Review James Curran presents such a historical guide for helping Australia’s navigation of China relations today, seeking to address the tendency of ‘the stress of being in uncharted waters’ leading to an easy dismissal of ‘the relevance of what the past might offer.’

Specifically, it is a meticulous account of Australian political interaction with China from the CCP’s takeover in 1949 to mid-2022, focusing on Australian prime ministers but offering coverage of their cabinets, advisors, political oppositions, and public servants. Grounding each prime ministership in the prevailing political and economic wisdom of their times, Curran charts the ebbs and flows of Australia’s China relations, and how approaches under successive governments were shaped by national and international dynamics. Often, he finds, Australia’s approach to China was driven by anxieties about being ‘an isolated European outpost on the edge of Asia’ and in many instances ‘refracted through [Australia’s] alliance with the United States.’ A trend emerges—although Curran is careful not to overstate this—of swings during each prime ministerial period between vigorous reaction to real and perceived threats from Beijing followed by at least a degree of a shift toward some rapprochement with China.

Curran’s book was published a few months after the May 2022 election of the new Australian government, headed by the Australian Labor Party and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. It is worth asking, then, what light his research can offer for the present and future of the bilateral relationship. At first glance, and in fitting with the general theme of the book, the relationship looks to have taken another turn—away from the narrative, amplified by the prior Liberal-National government of China’s threats, and towards a more stable relationship, although one in which China remains deeply unpopular with the Australian public given its actions at home and abroad. Prime Minister Albanese met President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of last year’s G20 leaders’ summit in Bali, ministerial contact has resumed at the highest levels, and China’s economic coercion is starting to ease, even if that process has some way to run—assuming Beijing does indeed end such coercion. It is possible, too, that Albanese will visit China in October or November this year, which would also mark the fiftieth anniversary since his predecessor Gough Whitlam made the first prime ministerial visit in 1973. Albanese would be the first Australian prime minister to visit Beijing since Malcolm Turnbull in 2016.

But two qualifications should be added here. The Labor government, while modifying the tone of its rhetoric and highlighting the ongoing benefits of trade with China—the prime minister seems particularly fond of reminding journalists that Australia’s trade with China is greater than that it enjoys with the United States, Korea, and Japan combined—has nevertheless embraced the strategic assumptions of its predecessor. Ministers regularly point to the uncertainty created by China’s continued military build-up in regional waters and other areas, and Labor has stood steadfast alongside the very same pillars as its predecessor: the Quad, strengthened defense relations with Japan, and, most notably, the AUKUS trilateral security partnership and acquisition of nuclear submarines. Prime Minister Albanese is actually keen now to claim joint authorship of AUKUS with former Prime Minister Scott Morrison, saying he would have made precisely the same decision on the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines. Indeed, the proposed commitment was barely been subject to parliamentary debate, with the Labor Party making the decision to commit to the project ‘in less than twenty-four hours’ after they were first fully briefed on the matter. The Labor Party has emphatically locked in behind the alliance, with Defence Minister Richard Marles committing to moving cooperation between Australian and US forces ‘beyond interoperability to interchangeability’ during Labor’s second month in office. The alliance, he told a press conference following the Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations later in the year, ‘is essential to our worldview, it is completely central to our national security.’

The second is that the stabilization in relations has taken place against the backdrop of a Chinese attempt at a global diplomatic charm offensive—albeit one which has been met with skepticism. Limits to Beijing’s professed goodwill were on display last year as President Xi delivered a public dressing down of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after the closing session of the G20 following an alleged leak of an earlier conversation. President Xi said that ‘the outcome will not be easy to tell’ if there was no ‘sincerity’ in communication. But Chinese rapprochement with Australia matches its attempts to mend fences with the European Union, broker an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, deepen ties with Central Asia, and establish itself as a principal donor in the Pacific. The Chinese response to both the AUKUS announcement in San Diego in March and to the release of the Defence Strategic Review has been relatively muted, perhaps suggesting that it is not too alarmed by submarines whose delivery time is not only uncertain but a long way into the future. But the bulk of Beijing’s wolf warriors, it seems, has, for now, been sent to the back of the diplomatic pack. It is not yet clear how both sides advance beyond Australia’s policy objective of ‘stabilization’, but the old era of closer Australia-China ties is most unlikely to return, particularly as Beijing continues its advance down an increasingly repressive and authoritarian path under Xi.

Curran’s book is also an important corrective to the notion that Australia is just now ‘waking up‘ to the challenge from China on multiple fronts. Australian China policy, particularly during its earlier years, has been persistently charged with blind naivety. The Australian newspaper’s foreign editor Greg Sheridan, for example, described Gough Whitlam, the Australian Labor prime minister who normalized relations with Beijing, as having ‘idealized and romanticized our relationship with a ruthless communist dictatorship.’ Australian historian Edmund Fung argued that Bob Hawke, the Labor leader who enjoyed unprecedented access to the Chinese leadership during his prime ministership, took an overly ‘benign view of Beijing’s strategic and security interests in the region.’ This brand of critique gained particular prominence beginning in 2016, during the most recent chapter of Australia’s China debate. A variation of this assertion was most recently articulated in a March series this year by the Sydney Morning Herald/The Age news outlets which warned readers that ‘Australia’s government has not told the people about the seriousness of the threat the country faces [from China].’ Curran shows, however, that since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1972, the Australian political establishment has always, in some form, been cognizant of the challenges that China presents, with even the most euphoric periods shot through with a thread of anxiety.

Curran shows, for example, that while Whitlam sought a ‘new international outlook’ and a ‘new era of regional belonging’ with China as the central symbol of this aspiration, he was also keenly aware of limits to burgeoning bilateral relations, underlining in his charter letter to Australia’s first ambassador to China, Stephen FitzGerald, that Australia was ‘not in any sense ‘committed to China’’ nor ‘willing to give China uncritical support.’

Curran also reveals robust Australian bureaucratic resistance to overly close relations with China during this period, given its clearest voice in a 1980 Department of Foreign Affairs planning paper which laid out apprehensions about the policy dilemma posed if a stronger China changed direction, that is, if it ‘renounced its involvement with the West and pursued a policy of self-reliance.’ It concluded that there was a need to accept that the relationship was based on ‘a partial, and possibly temporary, congruency of interest, which is itself based on a shared perception of what constitutes the major threat to that stability.’ At this stage, the unifying threat was Soviet aggression.

Even throughout the close bilateral ties of the Hawke years, in which Hawke said that he believed Australia and China saw ‘eye to eye on a great majority of issues,’ Australia refrained from seeking out a special relationship with China equivalent to the type it enjoyed with the United Kingdom and the United States. The Tiananmen Square massacre also forced a confrontation of views within Australia’s China community on hopes for Chinese political reform. And while Hawke’s successor, Paul Keating, was of the view that ‘the way to respond to China’ was ‘to fully engage it,’ he was forthright about the fact that nations were entitled to ‘make prudent arrangements… that have an eye to their security.’ These considerations underpinned his 1995 security agreement with Indonesia, a nation assessed by Australia as expansionist and volatile before that point.

Elegantly written, richly detailed and free of ideological bias, Australia’s China Odyssey is a welcome clinical appraisal of the Australia-China relationship over the years. The work focuses in a disciplined manner on an exploration of the Australian perspective, and while the book precisely articulates this scope, in service of its emphasis on the importance of context, it could have been strengthened by the inclusion of some further discussion on parallel thinking and developments in China during each of the political periods explored. Of course, that source material would be more limited.

Curran elevates Australia’s discussion on China relations by jettisoning the tendency towards myopia in focusing narrowly on the immediate present without due regard for the past—testing assumptions, and looking to history to help inform, but not dictate, how Canberra approaches one of Australia’s most pressing foreign policy questions.

Elena Collinson is head of analysis at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney (UTS:ACRI).