The contradictions of the PRC’s leadership ambitions

November 18 2021

By Mark Beeson

Note: An edited version of this article appeared in The Canberra Times on November 18 2021.

In the aftermath of the recently concluded COP26 meeting, it’s not hard to see why many people - especially the younger variety - are disappointed and disillusioned. Despite lofty ambitions, not much of significance has changed, especially following India’s and the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) determination to water down a proposed commitment to phase out coal.

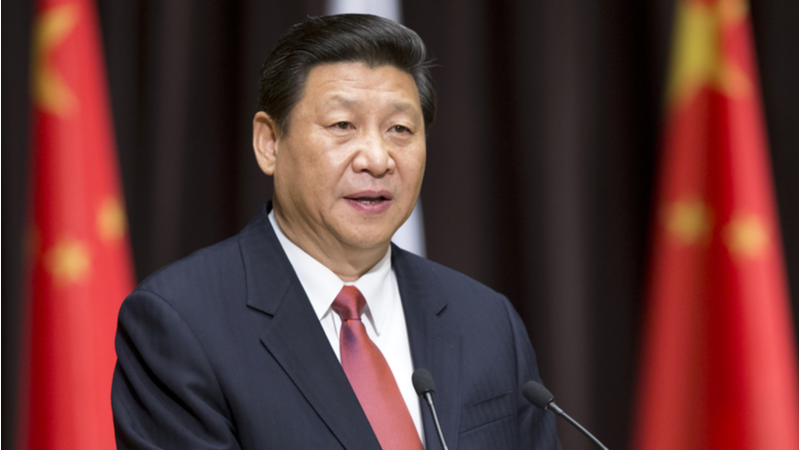

It might seem an odd time to be thinking about the PRC’s capacity to lead on climate change or anything else for that matter, given the growing alarm in Western strategic circles about the threat the PRC poses to American primacy and the fabled rules-based international order that has supposedly kept the world safe for more than half a century.

Even if we overlook the fact that the US, along with its trusty Australian ally, was involved in needless, counter-productive wars in Asia and the Middle East, and - unlike the PRC - weren’t above invading notionally sovereign states when they felt it necessary, the Anglosphere’s contribution to international stability has been uneven, to put it kindly.

Indeed, if we regard climate change - rather than more traditional strategic threats - as the greatest danger the world has ever faced, Australia’s contribution in particular has been parochial, instrumental and embarrassingly disingenuous. Under such circumstances any country that is actually trying to address the greatest collective action problem we have ever known deserves a hearing, especially when they really do have the capacity to make a difference.

Despite the fact that the PRC continues to build coal-fired power stations, it’s also the world’s biggest investor in green energy. This highlights a couple of underlying structural realities that will shape domestic and foreign policy in the PRC for the foreseeable future.

First, given that the legitimacy and authority of the Chinese Communist Party is bound up with keeping the economic development project on the road, the PRC’s leaders may feel they have no option other than to prioritise continuing economic growth at all costs. Second, in that context there is only so much that renewables or even nuclear power can do in the short-term. All of which means coal and the regions that depend on it remain politically important; just as they do in Australia and the US, of course.

What sets the PRC apart from its Anglosphere rivals, however, is the relative modesty of Xi Jinping’s vision about where the economic side of the PRC’s rise is leading. The stated aim is to create a society of ‘moderate prosperity’, which is notably at odds with the standard international rhetoric about the need to keep economic development going at all costs.

Sceptics will no doubt point out that the PRC is on course to become the largest economy in the world in the near future – something that will no doubt be widely celebrated by the people in the PRC as a whole. But it will be interesting to see what the accompanying government rhetoric looks like: it does seem as if there is a realisation in the PRC that there really are limits to growth.

In such circumstances, the most that any of us can hope for, whether we live in the North, the South, or somewhere in between, is a form of sustainable ‘moderate prosperity’. Even that may be forever out of reach for the world’s legions of impoverished, displaced and insecure who find themselves threatened by climate change and state failure of course. But as a collective goal for humanity it looks rather more appropriate than the fantasy of endless growth and indefinitely rising living standards.

But even in the unlikely event that idea of moderate prosperity catches on as a suitable collective goal for humanity, it will be difficult to achieve in the PRC, let alone anywhere else. After all, the PRC has become one of the most successful - in the short-term, at least - capitalist economies in the world, albeit of a decidedly state-led variety. The PRC’s expanding, very rich capitalist class may not take kindly to having their power and privileges circumscribed.

Unlike in the US, however, Xi has developed a more inclusive rhetoric in this regard, too. The idea of ‘common prosperity’ is the suitably socialist sounding counterpart to the ‘moderate’ variety. Given that the PRC now has nearly as many billionaires as the US, though, this may never amount to more than a rhetorical flourish with suitably Chinese characteristics.

And yet this could prove to be a lost opportunity for the PRC, and perhaps the world, if Xi doesn’t follow through. It is becoming increasingly clear that the current global developmental model is inequitable and unsustainable. The one unambiguous positive to come out of COP26 was the possibility that the PRC and the US may start a serious dialogue about ways they can cooperate. We desperately need a radically different basis for great power relations if we are to survive at all, never mind in something like a civilised state.

Anyone who can come up with a unifying rhetoric that is at least more appropriate in principle for our collective existential dilemmas deserves a hearing - especially if they are actually in a position to do something about it.

Professor Mark Beeson is an Adjunct Professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney.