China–Australia relations on cloud wine

April 05 2024

Note: This article appeared in the East Asia Forum on April 5 2024.

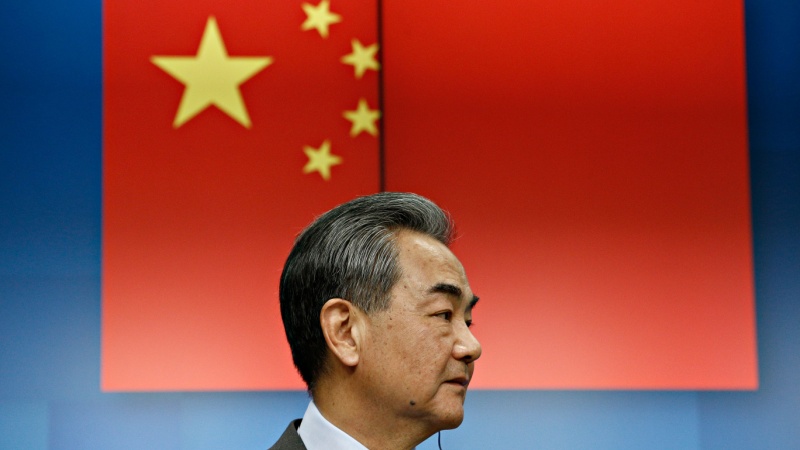

Cordial bilateral exchange between Canberra and Beijing continued when Australia received China’s top diplomat Wang Yi for a three-day visit in late March 2024, underlining a markedly improved, if still fragile, relationship after years of absent high-level dialogue and trade punishment inflicted on Australia by Beijing.

The most senior Chinese official to visit Australia in seven years, Wang met with Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong for the seventh Australia–China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue, as well as with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton and Shadow Foreign Minister Simon Birmingham.

Immediately before his visit was formally announced, China’s Ministry of Commerce made public an interim draft determination outlining the ‘proposed removal’ of Beijing’s punishing tariffs on Australian wine. Days later, Australian Minister for Industry and Science Ed Husic accepted a recommendation made by Australia’s Anti-Dumping Commission to discontinue anti-dumping measures against wind towers from China. Though Senator Wong rejected the suggestion that these actions amounted to a trade quid pro quo, these decisions cultivated a relatively positive atmosphere in the lead-up to the trip.

During the visit, there was nary a whisper of the ‘wolf warrior’-style diplomacy Mr Wang had advanced in previous years — his particular brand having been described as ‘biting’ and ‘acerbic’ — with official and unofficial exchanges variously characterised as ‘polite’ to ‘assiduously positive and forward-looking’. Indeed, his comportment appeared to give form to Beijing’s new diplomatic vision, set out during a party meeting in December 2023 — one that ‘foster[s] new dynamics in the relations between China and the world’.

The logistics underpinning the Chinese Foreign Minister’s trip also highlighted a further centralisation of decision-making in Chinese diplomacy and tighter management of diplomatic choreography, limiting opportunities for public disapproval. As an ABC News analysis pointed out, Wang’s itinerary was planned by the Chinese foreign ministry, bypassing the traditional diplomatic channels of the Chinese embassy in Australia — an ‘unorthodox approach’ that was ‘different from previous visits’. Further, Wang declined to attend a joint press conference with his Australian counterpart following their meeting, usually routine for visiting senior representatives.

Moving forward, Australia will likely be dealing with a Chinese diplomatic apparatus that is even more rigid, more activist and perhaps more unpredictable, subject as it is to greater control by Chinese President Xi Jinping.

During his engagements in Australia, Wang evinced a foreign policy approach that had a distinct focus on economic and business ties. This was likely an attempt to consolidate support in at least one corner of the West as the European Union drives forward its de-risking strategy and the United States pushes a partial decoupling. Australian restrictions on Chinese investment were the main Chinese concern put forward during the meeting. Engagement with senior Australian industry figures was prioritised in Wang’s tight schedule, with him attending a private roundtable organised by the Australia–China Business Council that predominantly comprised business leaders as participants.

The Wong–Wang exchange civilly covered the expected ground vis-a-vis Australian and Chinese interests and concerns. But again it accentuated the expectations gap — one that first became evident in the second half of 2022 — between Canberra and Beijing’s respective ambitions for the bilateral relationship.

Beijing’s firm eye on the future was underlined by Wang’s call for ‘no hesitation, no yawing and no backward steps’ in the bilateral relationship. He stated that ‘both sides should strive to make steady, good and sustained progress’ as ‘the course forward has been charted’.

Wong, while stating that Australia desired a ‘mature and productive relationship’, expressed a markedly more cautious stance. She stuck to the Albanese government’s now well-established aim of ‘stabilising’ the relationship, noting that ‘there is more to be done’ in this regard. She told her counterpart, ‘dialogue enables us to manage our differences, we both know it does not eliminate them. Australia will always be Australia and China will always be China’.

In centring dialogue and exchange, the Albanese government’s stabilisation agenda has afforded it flexibility in navigating the Australia–China relationship. In perhaps the most fully fleshed out articulation of how the Australian government envisions a stabilised relationship with China, Prime Minister Albanese in October 2023 said it was one in which there were ‘no impediments to trade’, that had more ‘honest and open’ as well as ‘more regular’ dialogue and that it had ‘no surprises’.

But limitations to even this relatively modest intent are already apparent. The suspended death sentence given to Australian citizen Yang Hengjun in February appeared to be unexpected news to the Australian government. Albanese said the government had conveyed to China ‘our dismay, our despair, our frustration, but to put it really simply, our outrage at this verdict’. And in 2023, only one week after Albanese’s warm reception in China, Australian navy divers were exposed to sonar pulses from a Chinese warship in the East China Sea, an incident for which Beijing continues to deny responsibility.

The core of Australia’s Defence Strategic Review 2023, its closer maritime cooperation with the Philippines, as well as Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles’ call in late 2023 to strengthen collective deterrence of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait, speak to a pervasive unease and mistrust. Further, in March 2024, the Australian government joined the United Kingdom and other partners in expressing ‘serious concerns’ about malicious cyber targeting of UK democratic institutions and parliamentarians by China state-backed actors.

Further challenges are on the immediate horizon, not least a possible Trump administration in 2025 making more demands of Australia, particularly if Trump implements an aggressive economic containment of China and dilutes US involvement in the bolstering of Australia’s defence capabilities via AUKUS.

Stabilisation has proved to be an effective policy for now, engendering much-needed dialogue and exchange, allowing for the effective management of differences. This is crucial for peaceful coexistence, especially as great power competition intensifies and for the resolution of some irritants in the bilateral relationship, most recently highlighted by the official removal of China’s duties on Australian bottled wine. But whether it suffices in the longer-term remains to be seen.

Elena Collinson is head of analysis at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney (UTS:ACRI).