China's 'rule of law in international relations'

August 01 2018

Note: This article appeared in the Lowy Institute's blog, The Interpreter, on August 1 2018.

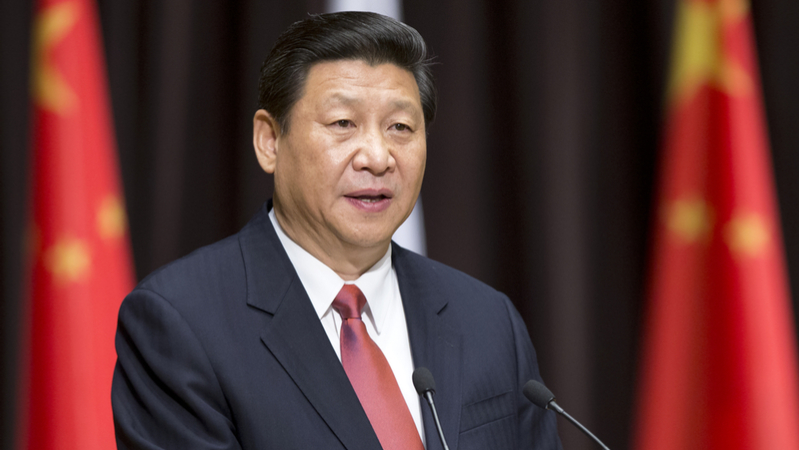

In 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping introduced the term 'rule of law in international relations' to describe the Chinese government’s vision for the interaction between states within the international order. He said:

We should jointly promote the rule of law in international relations (国际关系法治化). We should urge all parties to abide by international law and well-recognised basic principles governing international relations … There should not be double standards when applying the law. We should jointly uphold the authority and sanctity of international law and the international order.

The term is related to – but used in distinction from – existing concepts of international law (国际法) and international rule of law (国际法治). The Chinese government’s application of 'rule of law' to 'international relations' specifically indicates a new concept in its global governance lexicon.

But what does it mean?

Xi’s use of the character hua (化) here is instructive: it signifies a change in state, meaning the Chinese government does not believe international relations are characterised by the rule of law, and this requires revision.

The reference to 'double standards' is also telling. The Chinese government frequently accuses other states of having 'double standards' when they criticise China’s human rights record and its occupation or militarisation of features in the South China Sea. Invoking the 'rule of law in international relations' could serve as a more sophisticated rebuke.

The timing of the introduction and dissemination of 'rule of law in international relations' coincides with China’s domestic push for 'rule of law'. The Fourth Plenum of the 18th Party Congress in October 2014 passed a set of reforms to the judicial system and government, including provisions ensuring greater accountability of party members and officials and the centralisation of the court system, all under the auspices of 'socialist rule of law'. These reforms are explicitly Party-led: they emphasise that “the Party’s leadership is … the most fundamental guarantee for socialist rule of law in China”.

Following the 18th Party Congress, Foreign Minister Wang Yi praised Xi’s introduction of 'rule of law in international relations', writing in an opinion piece for state media that:

diplomacy is an extension of domestic politics; China, with its firm commitment to promote rule of law internally, is inevitably a firm protector and active builder of international rule of law.

This strongly suggests that the Chinese government’s understanding of the rule of law in its domestic context informs its international approach.

This could be concerning, because China’s understanding of 'rule of law' is fundamentally different to Australia’s and that of the UN. This is why the term is sometimes translated as 'rule by law'.

For Australia, rule of law constitutes a constraint on the exercise of unlimited power, separate from the executive arm of government and applied equally to all citizens. The UN defines it as:

a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards.

The term 'rule of law in international relations' remains poorly defined. Despite facing resistance, China has had some noteworthy success in its attempts to introduce obscure concepts into international discourse.

In March 2018, Australia abstained from voting on a UN Human Rights Council resolution endorsing the terms 'mutually beneficial cooperation' and 'community of shared future', protesting that the resolution 'seeks to embed new, undefined concepts into the human rights discourse' which are 'not clearly understood in the Human Rights Council, or in other UN Forums'. The resolution passed.

The Chinese government may attempt the same with 'rule of law in international relations', which it has linked to the idea of 'mutually beneficial cooperation'. In 2015, then Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin remarked that states must establish 'an international order with the rule of law as its dominant feature'. He added that:

China is committed to the democratisation and development of rule of law in international relations, and building a new type of international relations with mutually beneficial cooperation at its core.

China has already begun promoting the notion of 'rule of law in international relations' at the UN.

In its 2017 national statement at the UN General Assembly, China argued that the UN should 'follow current trends and work to make international relations more … rule-of-law-based'. It is interesting to note that the English version in fact mistranslated 'rule-of-law-based' as 'rules-based'. While 'rules-based international order' is familiar to Australia and its partners, China tends not to refer to international relations or the international order as 'rules-based', except in reference to the World Trade Organisation.

For now, no one is paying much attention to China’s idea of the 'rule of law in international relations'. But understanding it may be the key to comprehending what a China-led international order could look like.

Simone van Nieuwenhuizen is Project and Research Officer at the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.